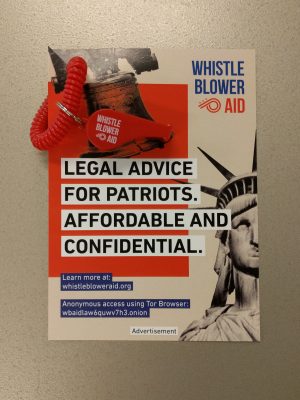

On Monday, a former top State Department official who blew the whistle three years ago on what he saw as overzealous surveillance announced a new non-profit law firm, Whistleblower Aid. Unlike most other whistleblowing organizations, however, Whistleblower Aid is employing a few crucial digital tools to help, including Tor and SecureDrop—and it’s entirely pro bono.

“We’re also helping people go to Robert Mueller if they have evidence of crimes by senior officials,” John Tye, the former official, told Ars, referring to the Department of Justice special counsel that is currently investigating possible collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia during the 2016 presidential election.

Tye’s partner is Mark Zaid, a well-known national security attorney based in Washington, DC. Unlike most modern law firms, which conduct nearly all business by phone and e-mail, Whistleblower Aid outright eschews these methods.

“You should only discuss your case with a lawyer that you trust, over a secure channel,” the group’s site proclaims. “Never use e-mail, web forms, regular phone calls or text messages. In-person meetings should be conducted away from all electronic devices.”

In addition to its regular webpage, Whistleblower Aid also maintains a .onion URL as well: http://wbaidlaw6quwv7h3.onion/.

“We want to earn the trust of people who have been 20-year veterans at the NSA,” Tye continued. “It’s the only way we felt that we could provide the security that our clients would want.”

Perhaps more importantly, Whistleblower Aid requires the use of SecureDrop—a Tor-enabled submissions system that was originally designed for journalists.

“You and I know the last 10 years it’s been one data breach after another, private corporations, government agencies, the Office of Personnel Management hack, even the NSA is getting hacked and having their own tools stolen,” Tye added. “So digital security is at the front of everyone’s mind. It was at the front of my mind at State and I didn’t want to put my complaint in an e-mail or a call. We are creating the highest level of security that we can create and that’s to build the trust of people who have very sensitive information.”

Three years ago, in the aftermath of the Snowden revelations, Tye told anyone who would listen to focus on the authority that the federal government claims under Executive Order 12333—”twelve triple three.”

When he first stepped into the limelight in the spring of 2014, John Tye tried really, really hard to stay within the official channels of whistleblowing. He didn’t send a cache of documents to WikiLeaks. He didn’t leak selected materials to journalists. Rather, he took the slow, methodical route—filing formal complaints with various Inspector General offices and sending letters to Congress. He only received perfunctory responses, nothing substantial.

Then, in July 2014, Tye publicly aired his grievances in the op-ed pages of The Washington Post. The piece was even submitted for pre-publication review by the State Department and the NSA to ensure the op-ed did not contain classified information, but neither agency appears to have changed a single word.

In the three years since he came forward, Tye admitted that the government’s policies with respect to 12333 hadn’t “measurably changed,” but he added that if he had chosen to leak outside of official channels, “I could have been prosecuted,” he said. “I’m not sure that doing it a different way would have solved it.”